How might a scientist-theologian conceive of the end of the world? How might his theology inform his science and his science his theology? John Polkinghorne’s book The God of Hope and the End of the World gives us one set of answers to these questions. His task is to use the resources of both science and theology to think through what it means to speak of the end of the world and what it means to hope for that end.

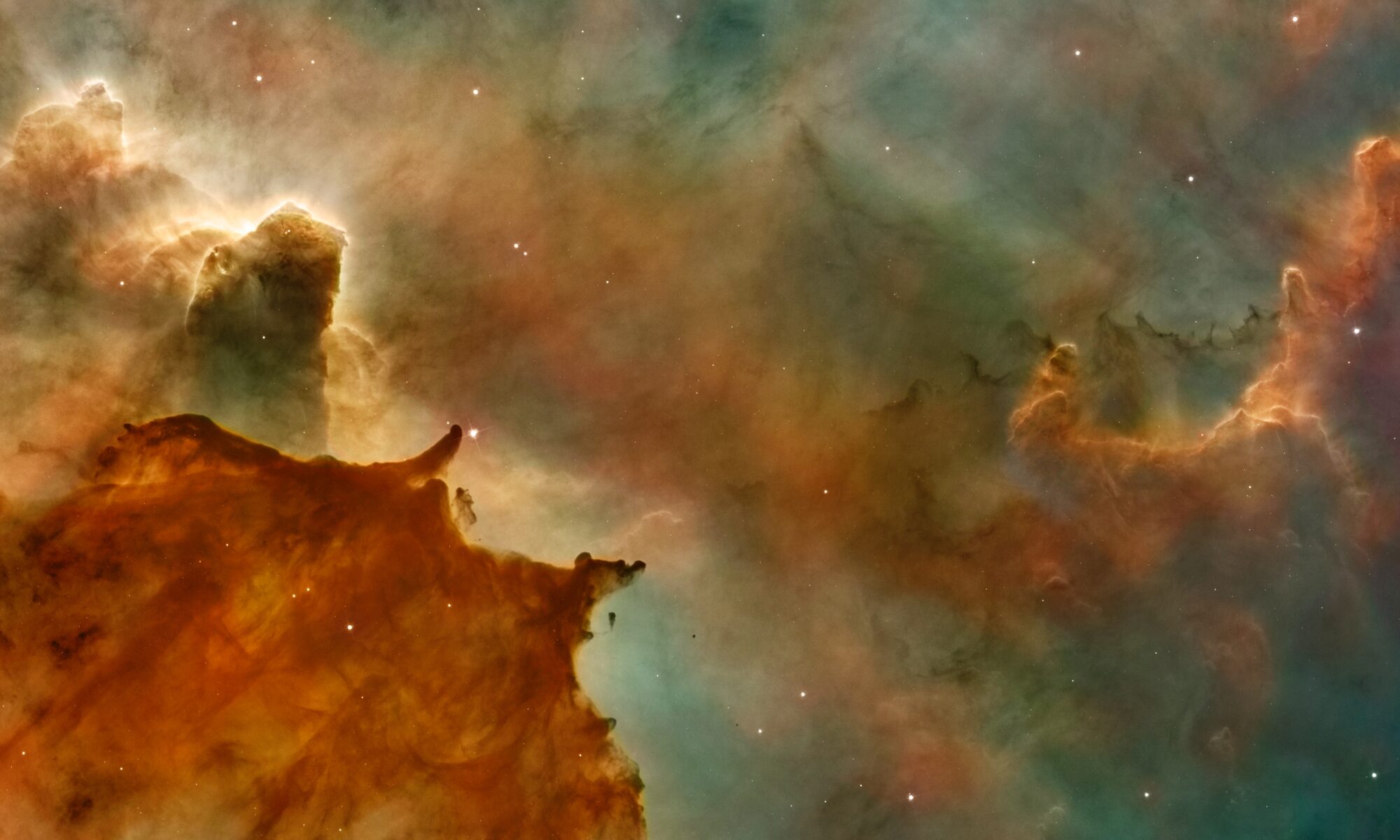

Bringing science into the discussion reminds us of something we might otherwise forget—the question of the end of the world is not just a theological question. Taken in purely scientific terms, scientists argue that the universe has two possible ends. Either expansion will win out and everything will freeze in the endless expanse or gravity will win out and the expansion will reverse so that all collapse into a Big Crunch. As Polkinghorne concludes, “From its own unaided resources, natural science can do no more than present us with the contrast of finely tuned and fruitful universe which is condemned to ultimate futility. If that paradox is to receive a resolution, it will be beyond the reach of science on its own. We shall have to explore whether theology can take us further by being both humble enough to learn what it can from science and also bold enough to hold firm its own sources of insight and understanding.”

In this summation, I hear a playful echo of Romans 8 when Polkinghorne says that apart from a theological understanding, all science can tell is that the world is “condemned to ultimate futility.” It is worth reflecting on Romans 8 because that chapter offers a bridge from the scientific understanding of the end to a theological understanding. Paul insists that the creation is in bondage to decay, thought not in vain, but rather in hope for the resurrection: “For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (Rom. 8:20-21). For Paul, and for Polkinghorne, Christ’s resurrection is not just a promise to humans about the possibility of resurrected life, but a promise to the whole of creation. God must do for his creation what he did for his Son—raise it up out of death.

What are the benefits of this approach? One benefit is that as a scientist-theologian Polkinghorne sees the interconnectedness of things. Even his discussion of judgement appeals to the interconnectedness of not just human beings, but of the whole of creation. God’s judgement, Polkinghorne insists, must take everything into account, all of creation. At the cosmic scale and at the human scale interconnectedness is vital. As Polkinghorne puts it, “One further thing needs to be said about judgment. So far we have spoken about it as if it were simply a process unfolding individuals and God. Yet, if there is a systemic and social dimension to sinfulness, as there certainly is, Miroslav Volf is surely right to emphasize that judgement also possesses a corresponding dimension, particularly when it is understood as being part of a redemptive process. ‘If sin has an inalienable social dimension, and if redemption aims at the establishment of the order of peace…then the divine embrace of both victim and perpetrator must be understood as leading to their mutual embrace.’”

Another benefit—Polkinghorne thinks in vast time horizons, and so considers our place in the story at the scale of billions of years and in terms of ever expanding space, which means he is not bothered by what some take to be the Lord’s delay in bringing about the end of time. Our hope is in the Lord, not in a particular timeline. And yet science can help us expand our hope beyond ourselves because science helps us see that God’s world is much more than our little planet. But science itself is not hope. With the cosmic horizon science give us, we can marvel at the fruitfulness of creation, be awed at the fittingness of things, but neither marvel nor awe is hope. The end to which we move must be matter of hope, hope that God will keep his promise to do for us and for creation what he did for his Son—raise it all up at the last. This is a truly marvelous thing to hope in and yet it is what is promised. Polkinghorne to that end, quotes Bouchard, “that the cosmos will be slave to us is impossible; that we and the cosmos can be servants to each other is conceivable; that God will enter the suffering of slaves and servants and lift up their lives into God is what is promised” (32).

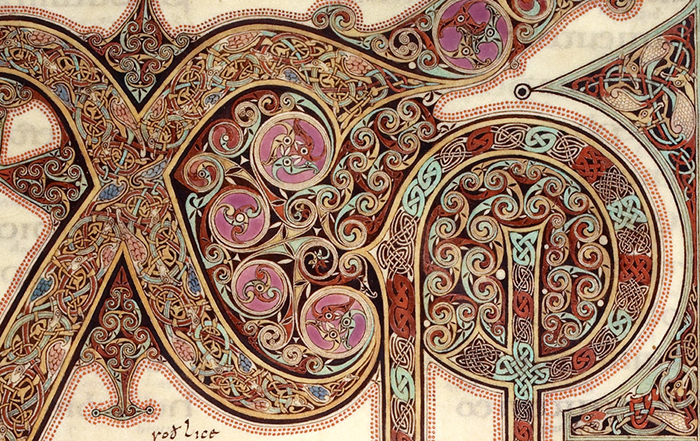

How do we practice hope, which is something much more than a feeling or a psychological disposition? Polkinghorne reminds us that the sacramental life of the church enacts our hope that the God of the past who has acted in history is also the God of the future who will keep his promises. The sacraments bear witness to the past by drawing us into the drama of the covenant life and point to the future when the promises of the covenant are fulfilled in their totality. And so while the sacraments are of this creation, and indeed mediate God to us through means of water, wine, and bread, they also enact the promised future of the new creation. Polkinghorne puts it this way—“This world is one that contains the focused and covenanted occasions of divine presence that we call sacraments. The new creation will be wholly sacramental, suffused with he presence of the life of God.” Therefore, to embrace the sacraments is to embrace hope, hope that this creation meditates the presence and promises of God to us and that this creation points beyond itself to a new creation. And we must embrace hope, for “those who embrace hope place themselves in the hands of the Lord of the open future. To do so is an act of total commitment to the One who is faithful.”