My friend Seth Wieck has recently started a newsletter, which he fills with his drawings, his writings, and his insights . It is lovely, and you should subscribe.

In his most recent newsletter, Seth links to an interview he did with the writer Nathan Poole. (Here is a link to the full interview.) The section of the interview that Seth highlighted in his newsletter is particularly striking for many reason, but especially around the theme of naming:

“There was a moment in my life, when I was out walking my dog, that I suddenly became aware of the fact that I was surrounded by trees, but that all I had to understand them was a singular category, “tree.” As in there’s a tree, and there’s another tree. It made me sad. And yet, in spite of the fact that these life forms were not only sustaining life on our planet, and the most ubiquitous form of life there is, I had no way of differentiating one from the next. It occurred to me that I would like to be able to call them by their names.

In many ways, this is the experience of Christians in the South, where the culture is saturated but not centered, in religion. They are offered one modality of faith, and it flattens the world. It propagates and prosecutes willful blindness, in the same way I once looked out onto a forest and just saw trees, trees, more trees. It’s not that I have a problem with the word “God” but that I wanted the experience of God to not be essentially gnostic, as in, God is in heaven and I need him in order to get there. I wanted to understand all the facets, the various ways God can be experienced, here and now.”

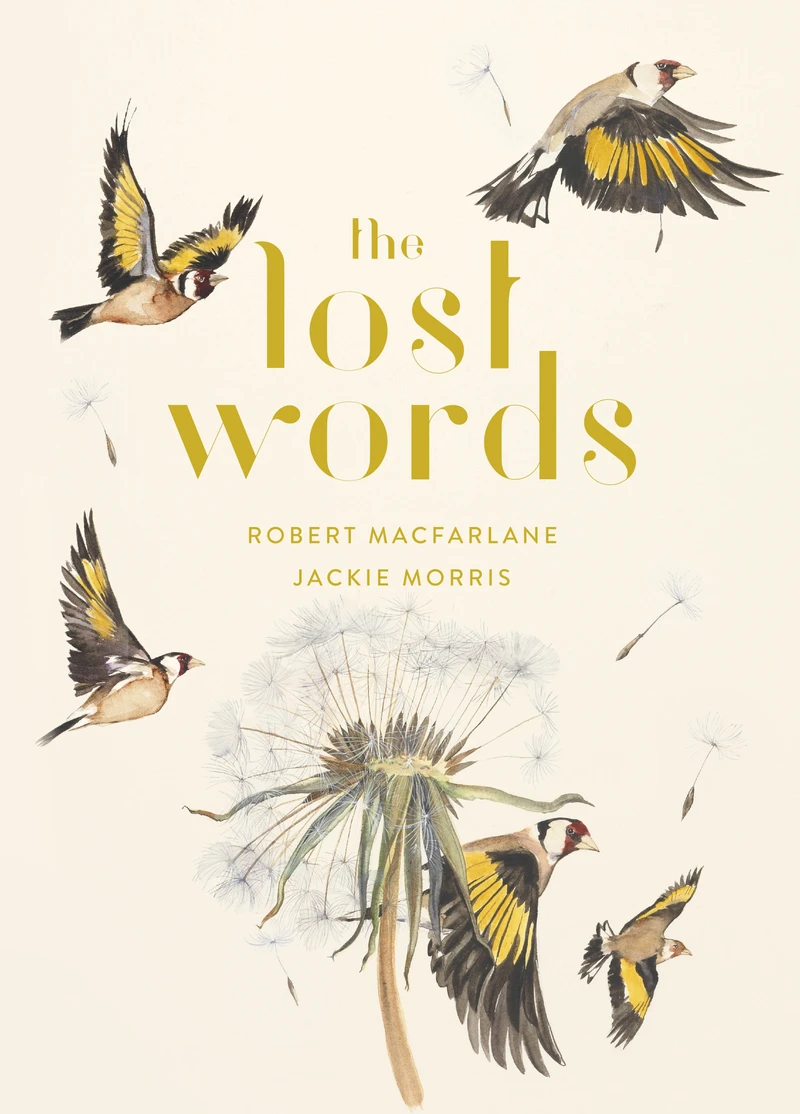

Poole’s remarks about knowing the names of things put me in mind of the beautiful children’s book The Lost Words by Robert Macfarlane.

The book’s poems and illustrations seek to recover lost words, words for the natural world, especially certain words that had been removed from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. The book is a vivid reminder to children and to adults alike that to lose the name of a thing is to lose something of the thing itself. And such losses can be devastating indeed. The implication of Poole’s line of thought is that to know the true names of things might help us better know God.

And indeed the conviction of much of the Christian contemplative tradition is just that, namely that contemplative receptivity of the world as gift in all its particularity can be a means to receiving God himself, to learn the name of God. If this is even remotely true, then to lose our sense of the world is to lose God, a claim that Balthasar makes again and again throughout his work on theological aesthetics.

To move a step further, it should not be surprising that at the heart of much mystical theology centers on meditation on the divine names of God. Dionysius the Aeropagite’s endlessly frustrating yet beguiling book of mystical theology is called just that The Divine Names. Such seeking, seeking after the name of God, is not fanciful. It is dangerous business indeed. The revelation of God’s name to Moses shakes Sinai, and Moses’ face radiates the glory of even the merest glimpse of that unveiling.

Seeking the names of things can also be our own search for name, a quest to find a place within the world we are at pains to name. Adam’s loneliness is made more acute by his naming of the animals because he sees that there is not yet one for him, and his naming of Eve after the fall, is a kind of receiving of himself. Jacob wrestled with God, and in his travail he sought a blessing, but received a name instead. To be named by God is the blessing beyond all blessings.