One recurring theme on this blog is the necessity of contemplation. In my study of Balthasar especially, and in encountering the tradition through him, I have been struck again and again by the central place of contemplation not just in Christian spirituality but also in Christian theology. If the statement that theology grows out of contemplation does not seem immediately apparent to you, you are not alone. One of Balthasar’s continual laments is the bifurcation of theology from spirituality and the resulting expulsion of contemplation from theology. But Balthasar’s own work and his re-presentation of the Christian theological tradition shows again and again that the really meaningful theology of the church has been forged in the crucible of adoration and obedience, in word it has been birthed from contemplation.

Balthasar’s contention is that there is no truly deep and meaningful theology which does not come from a place of prayer, particularly contemplative prayer. But his argument is deeper than that because contemplation isn’t meant for just the “Spiritually” and “Theologically” inclined. No, Balthasar insists, in his book on prayer, contemplation is the birthright of everyone. So while I have come to see that contemplation is vital for the theological task, I want to make this broader point too. I have come to see that quite apart from theology, contemplation is central to being human, whether one is formally engaged in studying theology or not.

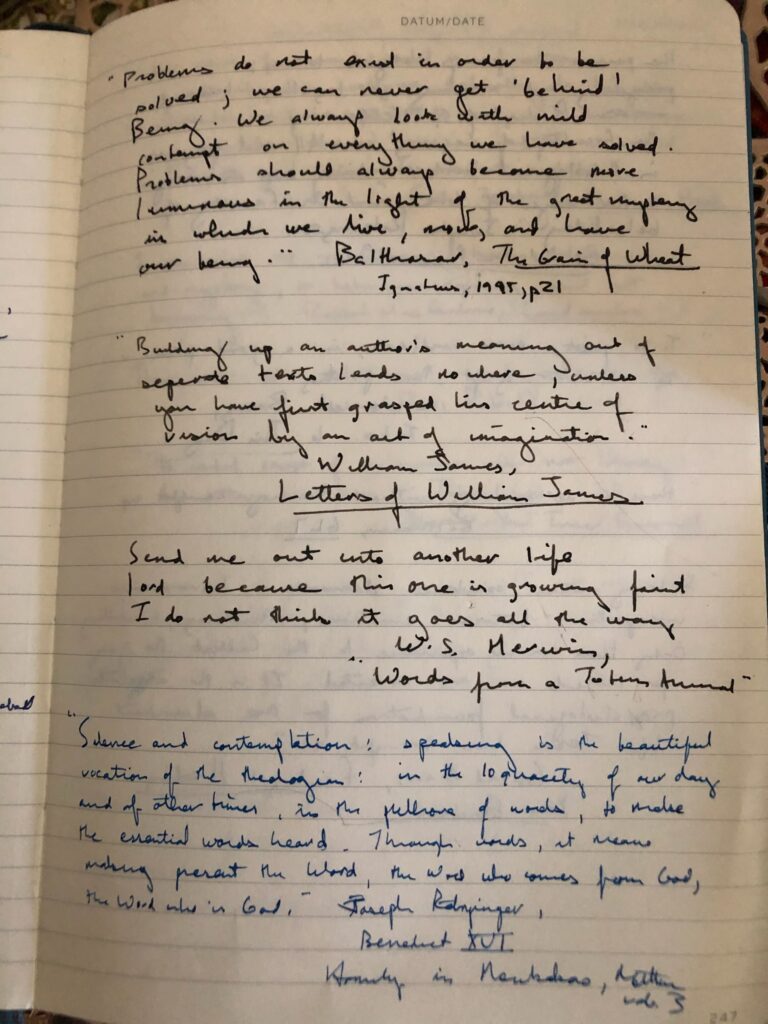

Another guide who has helped me realize this is Josef Pieper. Over the past few months, during the lockdown, I have been slowly reading Josef Pieper’s book Leisure, the Basis of Culture . It is in many ways the most helpful thing I have read in a long time, and most certainly the most helpful thing I have read in quarantine. Working from the Latin for the psalm, Pieper renders the famous phrase “Be still and know that I am God,” in this way: “Be at leisure and know that I am God.” Leisure is the contemplative stance, an openness to receive what is as it is, to receive the goodness of creation as a gift. This is perhaps always counterintuitive, but it is especially so in a time when I want to control things, to make things happen. Stillness, leisure, contemplation are all of a piece and are all aspects of intellectus (which Pieper, along with the Medieval tradition, distinguishes from ratio). Both intellectus and ratio are necessary and healthy aspects of the human mind, but Pieper’s concern is that we have surrendered ourselves to “total work” because we have come to believe that it is only ratio that matters.

But we need intellectus because it is through intellectus, through contemplation, that we experience the “useless” things of the world, that is things that are valuable in and of themselves, rather than things that are instrumental for getting me something I want. The “useless” ’things are what I actually need to live with integrity and with wisdom. Without such useless things, I have no chance of loving my neighbor, because after all my neighbor is never a means to an end, but someone to love.

Contemplation is a letting be and an openness to the goodness of Being, and ultimately to the one who is Goodness in himself. I have no time, I say. I have no space. I cannot. Oh but I may, and I must, if I want to receive what matters. There is a silence that must proceed any speaking that bears any weight at all.

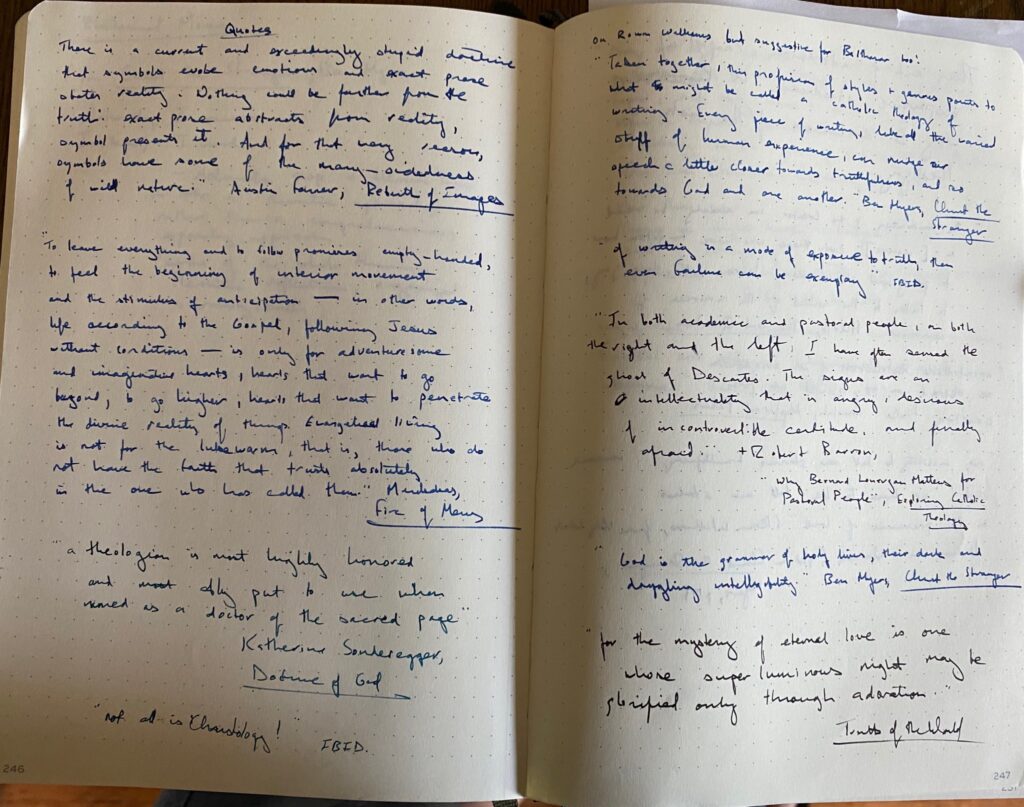

Austin Farrer too holds up the necessity of contemplation while lamenting its loss. (Iit is not a unique problem of the internet age!), and reminds

“The chief impediment to religion in this age, I often think, is that no one ever looks at anything all: not so as to contemplate it, to apprehend what it is to be that thing, and plumb, if he can, the deep fact of its individual existence. The mind rises from the knowledge of creatures to the knowledge of their creator, but this does no happen through the sort of knowledge which can analyse things into factors or manipulate them with technical skill or classify them into groups. It comes from the appreciation of things which we have when we love them and fill our minds and senses with them, and feel something of the silent force and great mystery of their existence. For it is in this that the creative power is displayed of an existence higher and richer and more intense than all.” Reflective Faith: Essays in Philosophical Theology

The truth is that the contemplative stance, the space within from which to truly see and to truly receive, is already within us. Yes, that room may have fallen into disrepair, but it is still there, and by grace it can restored and inhabited again. Or so says Balthasar:

“Man is the creature with a mystery in his heart that is bigger than himself. He is built like a tabernacle around a most sacred mystery. When God’s word desires to live in him, man does not need first of all to take deliberate action to open up his innermost self. It is already there, its very nature is readiness, receptivity, the will to surrender to what is greater, to acknowledge the deeper truth, to cease hostilities in the face of the more constant love. Certainly, in the sinner, this sanctuary is neglected and forgotten, like an overgrown tomb or an attic choked with rubbish, and it needs an effort—the effort of contemplative prayer—to clean it up and make it habitable for the divine Guest. But the room itself does not need to be built: it is already there and always has been, at the very center of man.” Hans Urs von Balthasar, Prayer

For a helpful discussion of some of these issues, I would recommend this episode of the Word on Fire podcast called “Distraction and Useless Things”.

For a more general introduction to Christian contemplative practice, I would recommend, Into the Silent Land by Martin Laird. It was given to me by a dear friend who was a man of prayer, if I have ever met one.